The Islandmagee witches

In Ireland, a witchcraft statute in 1586 resulted in very low numbers of trials, possibly only three.

The last witchcraft trial in Ireland took place in Carrickfergus in March 1711 when eight women were charged with witchcraft.

The scene of this alleged sorcery was Islandmagee, a small County Antrim peninsula town with strong Scottish connections. An 18-year-old girl, Mary Dunbar, had moved to the town in 1710 from Castlereagh in Belfast. She was invited to stay with her cousin, Mrs James Haltridge, who wanted some company after the death of her mother-in-law. Rumours within the community speculated that the old Mrs Ann Haltridge had died under suspicious circumstances - before her death, she believed she was the victim of a haunting, despite the fact that she was the widow of the Presbyterian minister of the area.

Having arrived to provide some support for her cousin, Mary Dunbar began to feel unwell and as the weeks passed, she began having fits, during which she would shout, swear and (shockingly to the local Presbyterian community) blaspheme. Mary claimed she saw the spectral forms of eight women during her fits and was able to name each one and give a description of them.

Soon, Mary was vomiting various items like feathers, yarn, pins and buttons. During her attacks, she would cry out about the women torturing her and claimed that they made her

““fall very often into fainting and tormenting fits, take the Power of Tongue from her, and afflicts her to that Degree that she often thinks she is pierced to the heart, and that her breasts are cut off””

Despite the efforts of local physicians and clergymen and even a counter-charm supplied by a Catholic priest, Mary continued to have fits. She named the eight women who were all then arrested and tried for witchcraft. In such a small community, the reputation of the accused played a big part in the trial. The “witches” were poor, some were disabled and none lived up to the contemporary standards of beauty. Three of them were accused of taking alcohol, smoking tobacco and swearing - all traits that were commonly considered unwomanly. Most of them did attend church but this counted very little as the case mounted against them.

Items vomited up by Mary were presented as evidence and the day before she was due to give her testimony, Mary was struck dumb. Physicians agreed that the cause of her illness was supernatural. The court was primed to believe the rumours.

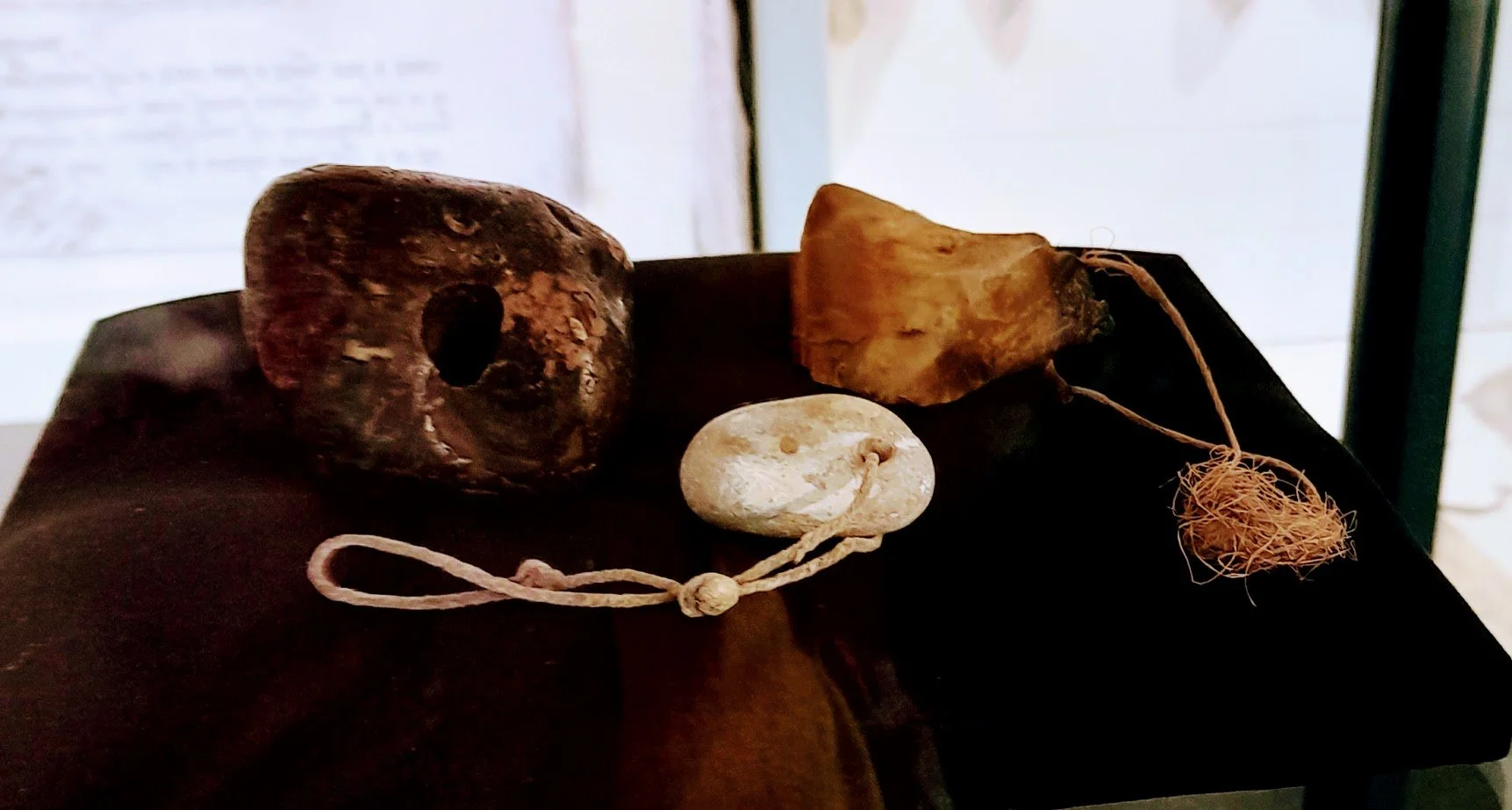

All eight women pleaded their innocence but were found guilty of witchcraft and sentenced to the pillory four times and jailed for a year. This might seem especially lenient but Ireland did not have the same culture of fear of witches as Scotland and England. In Irish culture, the witch was a more benign folkloric figure who mainly interfered with agriculture and was often referred to as a Butter Witch because all she was interested in was stealing your butter. Hanging up a ‘witch stone’ could effectively protect your livestock and property from the Butter Witch.

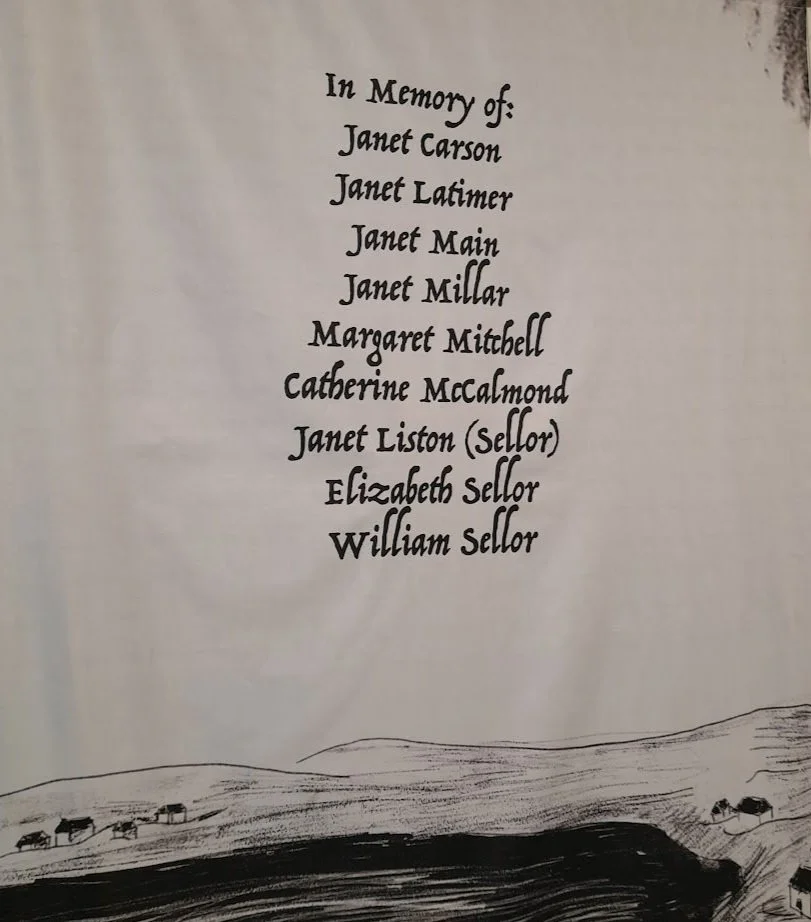

In similar cases in Britain, the “victim” of possession or witchcraft improved considerably after the witches were punished but in this case, Mary continued to have fits. The community could not now acknowledge that there might be another cause to her illness - the continuation must instead mean that there was someone carrying on the work the “witches” had begun. Mary soon accused William Sellor, a man whose wife and daughter were among the eight convicted. After resistance, William was brought before the summer assizes in September 1711. However, Mary Dunbar died before William’s trial took place. We don’t know what happened to William, although there is a possibility that he was executed for bringing about Mary’s death through witchcraft. Her death making the crime much more serious than the first trial.

The Irish witchcraft statute was repealed in 1821 but the lasting impact of this trial was passed orally from generation to generation in Islandmagee. Sites associated with the case, the rocking stone the witches supposedly danced on at night, the rock bearing the claw marks of one of the witches as she was dragged to court, were avoided by locals into the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the 19th century, a Carrickfergus historian created the myth that while in the pillory, the women were pelted with eggs and cabbage stalks, with one of the women losing an eye. William Sellor’s role in the story was largely neglected over time, with focus remaining on the eight women even though William may have been the last witch convicted in Ireland.

The story of this trial and these women is now more broadly commemorated with research projects, exhibitions and a small memorial erected in Islandmagee. However, even this proved controversial when a local councillor objected to the wording on such a plaque declaring the women ‘innocent’ of the crime they had been convicted of. The memorial now stands in Islandmagee, remembering the names of the eight women and one man in the last witchcraft trial in Ireland.

Further reading:

BBC, ‘Witches of Islandmagee plaque unveiled 300 years after trial’ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-65025035

Andrew Sneddon, ‘Witchcraft belief, representation and memory in modern Ireland’ in Cultural and Social History, 16.3 (2019) pp 251-270.