Isabella Tod

Isabella Tod was a woman ahead of her time, an advocate for the rights of the working class, for female education and suffrage. She was Belfast’s first feminist.

Isabella Maria Susan Tod was born in Edinburgh on 18 May 1836. Her parents were James Banks Tod, a Scottish merchant, and Maria Isabella Waddell, an Irish Presbyterian from Co Monaghan. Isabella had at least one brother, Henry, who became a merchant in London. There isn’t much known about Isabella’s early life, other than being educated at home by her mother.

By the 1860s Isabella and Maria were living in Belfast. Isabella was able to earn some money through writing for the Northern Whig and Banner of Ulster newspapers and Dublin University Magazine.

Isabella Tod

As a middle-class Presbyterian woman, it was expected that Isabella would get involved in charity work of some kind and there was a wide range of charitable work in Belfast. Through some of the visits Isabella made to the homes of the poor she became aware of the economic exploitation of women and this opened her eyes to issues surrounding women’s rights to own property or even keep their own wages. She organised a committee to promote amending property laws and became a advocate for women having control over their own wages. Her work was so widely recognised that she gave evidence to a governmental committee on the subject. Unlike other middle-class female activists of the time, Isabella was adamant that any changes in law not be restricted to the upper classes but must also apply to the middle and working classes.

Female Education

Isabella was also passionate that girls be given the same educational opportunities as boys. In 1867 she wrote a paper ‘On advanced education for girls of the upper and middle classes’ which was read on her behalf at a meeting of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science. Women could write papers but not present them. By this time, there were some opportunities for girls to receive a decent education through the National Schools (which offered free primary-level education) and through private secondary schools. Belfast had the Ladies’ Collegiate School from 1859 which was founded by Margaret Byers, a good friend of Isabella’s.

Margaret Byers

Founded Ladies’ Collegiate School, later Victoria College

However, many middle-class parents chose not to have their daughters educated in schools, preferring them to be educated at home. Isabella grasped that middle-class daughters needed to be educated in order that the working class might also allow their daughters to get an education. Middle-class parents wanted their daughters to be educated enough so they could read, write and run a household but not too much.

Isabella argued that these parents had expectations of

“all their daughters marrying, to all these marriages being satisfactory, and to the husbands being always able and willing to take an active management of everything. We shall not stop to discover whether such a state of things is even desirable. It is sufficient to point out that it does not and cannot exist.”

On the education of girls of the middle classes, 1874

Isabella established the Ladies’ Institute in Belfast in 1867 which offered classes to young women to improve their education and employment prospects. Lectures were provided on modern languages, history and astronomy among others.

Together with her friend Margaret Byers, Isabella travelled to London to meet with Disraeli’s government in 1878. They were successful in getting girls included in the Intermediate Education Act, legislation that set out an annual set of exams to be taken at the end of secondary education. The results from these exams were recognised by universities and professions.

Their attention then turned to university education, lobbying Queen’s College in Belfast to allow women to enter. While some professors gave lectures at the Institute, the idea of letting women be students at the College met with considerable opposition. It was only with the Royal Universities of Ireland, which provided more competition for Queen’s and led to a decline in student numbers that Queen’s allow women to enter. Gradually, faculties began allowing women to attend lectures throughout the 1880s although the statutes weren’t officially altered until 1895.

Queen’s College

Now Queen’s University, Belfast

Contagious Diseases Acts

Isabella did not stop there. Her activism for women’s rights was continually expanding.

In the 1860s pieces of legislation were introduction called the Contagious Diseases Acts. In a nutshell, this allowed for the compulsory inspection of women suspected of being prostitutes for venereal disease. It only applied to areas where there were army bases and large port towns, mainly because so many soldiers and sailors were out of action due to syphilis and gonorrhoea. In Ireland, the Acts applied to Cork, Cobh and the Curragh camp but Belfast had become Ireland’s largest port so there was a concern it could be included.

Contagious Diseases Acts

Legislation passed in 1864, 1866 & 1869

In 1870 Isabella founded a Belfast branch of the Ladies’ National Association, a movement set up to campaign for the repeal of the Acts. She also sat on the executive committee of the Association in London. This campaign focused on the fact that the forcible arrest, examination and possible detention only applied to women and not to men. There did not need to be viable proof that a woman was a prostitute, her being out on her own was enough in some instances. Any vague sign of venereal disease was used to detain the woman in a lock hospital and subject her to treatment, which would often induce horrendous side effects, or experimentation. This legitimised the double standard of sexual morality. For Isabella and her fellow campaigners, this was proof that the law was not on the side of women.

The movement was successful and the Contagious Diseases Acts were suspended in 1883 and then repealed altogether in 1886. This proved to Isabella that women needed and deserved the right to vote.

Votes for Women

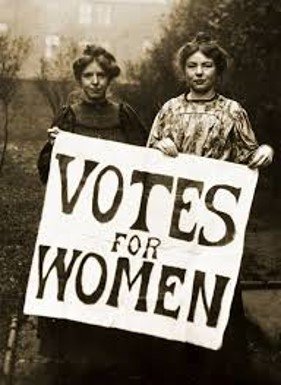

In 1871 Isabella organised the first suffrage society in Ireland, the North of Ireland Women’s Suffrage Committee. She was friends with leading English suffragists, such as Josephine Butler and Lydia Becker. Her speeches were widely reported and published. She toured Ulster campaigning for women’s right to vote. Inspired by her visit, Dublin set up its own suffrage society.

‘Votes for women’ became the main slogan for the women’s suffrage movement

She began with local municipal elections (like a town council) and won women the right to vote in Belfast in these elections in 1887 - eleven years before the rest of Ireland. She was also instrumental in getting women to be eligible for election as Poor Law Guardians of the workhouse. Isabella argued that caring for the poor had always been women’s work.

Part of Isabella’s belief was an innate sense that women were morally and spiritually superior to men. She argued

“experience showed that they [women] felt a deeper sense of responsibility resting upon them, and that they attempted to carry their religious principles into the common things of life to a greater extent than men did”

Women’s Suffrage Journal, 1 March 1883

Later Life

Sadly for Isabella she didn’t live long enough to see women finally getting the vote. She did however see the effects of a lot of her campaigning making a difference in Belfast. Alongside her national campaigns, Isabella was still active in local movements, particularly those aimed at women and the poor. She was a founding member of the Belfast Women’s Temperance Association, setting up a home for alcoholic women and another for destitute girls. She was involved in the Prison-Gate Mission which sought to meet women released from prison and help them find a safe place to live, often removing them from situations of violence. She said in 1893 that “My work soon taught me that drink is the main cause of poverty, and that in a yet larger measure it is the cause of domestic discord and misery.” (Wings, July 1893)

Isabella was recognised during her lifetime for the impact she had on her town and her country. In 1886 she was presented with a full-length portrait of herself as a sign of recognition for the work she had done for Ireland.

Isabella M.S. Tod by Marguerita Rosalie Rothwell

Ulster Museum

Her final campaign damaged her health as she travelled through England advocating against Home Rule for Ireland. She believed returning to an Irish Parliament would undo the achievements that had been hard-won in Westminster. She was also a staunch defender of the Union and of the Empire. This final campaign lost her many friends in the suffrage movement.

Isabella died at her home in Botanic Avenue on 8 December 1896 from a pulmonary illness. There is now a blue plaque at the location. How many walk past the place everyday not realising how exceptional the woman was and all the many ways in which she fought for the rights of women?

Further reading:

Queen's First Women - by HAPP Web

Tod, Isabella Maria Susan | Dictionary of Irish Biography